In Doll and Hill’s original research they concluded that the relative risk of lung cancer for smokers over 45, and smoking 25 or more cigarettes a day, was possibly as much as 50 times higher than it was for non-smokers. The Center for Disease Control in the US puts the relative risk at 25x for US males. This is, of course, is a material increase relative to the chances of contracting lung cancer as a non-smoker but then the chances of contracting lung cancer as a non-smoker are remote. Even a very large multiple of a very small number remains a very small number.

By way of demonstration of this point, we can look at the Statistics on Smoking, England for 2016 as published by the NHS. These data shows that that of the 459,087 deaths recorded in England in 2014, 77,800 were ascribed as “attributable to smoking”. It is worth noting that this is an estimate and not an actual figure, and is based on estimates for each of the possible illnesses identified as being related to smoking. Of all the deaths recorded, 28,826 were lung cancer deaths and 23,100 were ascribed to smoking. Lung cancer therefore accounted for 30% of all deaths ascribed to smoking, but just 5% of all deaths. Given the earlier discussion of the age at which lung cancer is typically diagnosed (over 70) and the age at which mortality occurs (just short of 74), we need to look back to smoking prevalence some 50 years prior to judge the risks of subsequently developing and dying of lung cancer. According to the Cancer Research data presented earlier, the prevalence of male smoking in the UK in the early 1960s was typically around 54%. Prima facie this would suggest that lung cancer has occurred in around one in ten smokers.

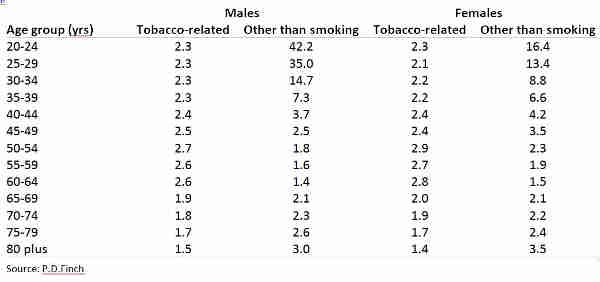

A similar outcome was observed by P.D. Finch in his analysis of Australian smokers, where he also argued that “Each year ever-smokers of both sexes and all ages are more likely to die of causes other than smoking than they are to die because of their smoking, and until they reach 40 years of age considerably more likely to do so”. In Table 1 below we show Finch’s estimates of the annual relative risks by age and sex that an ever smoker has of dying from a tobacco-related condition and from causes other than smoking rather than because of their smoking.

Table 1: Annual relative risks by age and sex, Australia, 1992, that an ever smoker has of dying from a tobacco-related condition and causes other than smoking

As can be seen, for men the risk of dying from something other than smoking is considerably higher when young, similar by the late 40s, lower until 65 and then higher again in old age. To put these relative risks into some context we also show annual death rates shown as percentages rather than the odds presented in the original work.

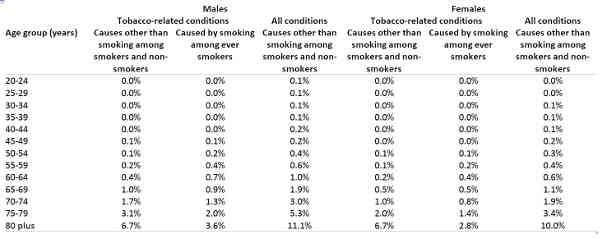

Table 2: Annual death rates: In tobacco-related conditions both for causes other than smoking, among smokers and non-smokers alike, and those among ever-smokers because of their smoking, together with those for all conditions, other than smoking, among smokers and non-smokers alike, by age and sex, Australia, 1992

Putting the relative risks against the absolute risks it can be seen that even for men of 50-54 when the relative risks of dying of a tobacco-related illness are at their highest (2.7x) the absolute risk of dying of a tobacco-related illness was just 0.2% or, expressed as odds, one in 487.

The important thing to stress is that smoking is risky, without doubt, but the absolute level of that risk is easily overstated by a focus on relative risks. The warning “Smoking Kills” can be true, but in a minority rather than majority of smokers.